Women in STEM

Last week I was at the 2016 Summit of the National Center for Women and Information Technology. It was an interesting conference in several ways (the large, mostly empty, slightly creepy desert hotel constantly evoked the warm smell of colitas), but mostly because of the very powerful keynote by Melissa Harris Perry.

She began by giving us a brief introduction to intersectionality and laying out the issue (a familiar one to this audience) of women’s underrepresentation in STEM, with some compelling (frightening) specifics.

For example, earlier this year, Chanda Prescod-Weinstein was awarded a PhD in theoretical physics at MIT. Nothing really surprising or unusual about that (although good news for Dr. Prescod-Weinstein), until you realize that Dr. Prescod-Weinstein is not just an African-American woman, she is one of only 83 African-American women to receive a PhD in physics or a physics-related field. 83. Not 83 in the past year, or 83 at MIT, or 83 with hyphenated last names. 83 African-American women with PhD’s in physics EVER. In all of American history.

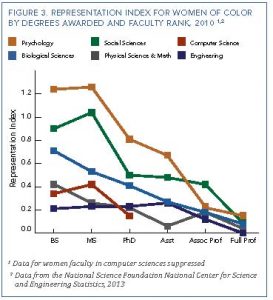

Then Dr. Perry showed us this graph (which I’d seen before, but which shocks every time) from the AAC&U study in 2010. (source)

Those lines show the numbers of degrees and faculty ranks for women of color in various fields. In physics, math, engineering and computer science, the numbers are low from the start. But look how all the numbers dive off a cliff when you get to the rank of full professor.

So the problem is real (and she had plenty more examples, some personal). And the audience knew it, and were more outraged still to hear all the examples and specifics. And Dr. Perry was very good about explaining how very many of the attempts to solve this problem (computer engineer Barbies, coding boot camps, job “opportunities” that don’t address the culture of organizations, internships or training programs that never lead to actual decision-making roles), even when they’re well-intentioned, are doomed to go nowhere, because they don’t address the roots and real causes of the problem. Which, of course, is deep, cultural, and complex.

But, to her great credit, Dr. Perry went even further than explaining the problem and critiquing unsuccessful solutions. (I was at first worried that this was going to end up as one of those “it’s a bigger problem and therefore we have to just throw our hands up in the air” talks) She provided a list of real practical steps, with deep reach and broad foundations, that could actually, systemically, successfully, pave the way to creating and improving real opportunities for girls and women of all kinds to participate in real ways in the STEM careers and academic pursuits in which they are underrepresented.

Here are those steps, as I captured them. Working from my notes, hastily scribbled, I am certainly missing and mis-paraphrasing some of what she said. But I thought this was real enough and strong enough to document.

- Fight voter suppression. This one clearly surprised the audience, as it seemed somewhat unrelated. But Dr. Perry’s link of underrepresentation to questions of policy and power and funding (controlled by the people who are most affected) made perfect sense.

- Reproductive justice and real sex education. Women can’t easily make the whole ranges of choices about their careers and educations if they can’t make choices about their bodies and families and partners.

- Comprehensive immigration reform. So that women can pursue opportunities globally.

- Cite a woman of color. Every time. In every publication, in every talk, always cite at least one woman of color. If you haven’t cited any, don’t assume there are none to cite. There are, and the fact that you don’t know of them is part of the problem, not a reason to continue the problem.

- Follow Black girl leadership. Don’t tell the girls what’s the “right” kind of STEM or of making, let them tell you. Reading, or rocking, or singing or painting, can be just as much a way to learn STEM as coding. Schools (and especially STEM programs in schools) need to stop acting like making art or music in school is some kind of weird distraction or waste of time. (STEAM not just STEM).

- Honor the different intersections of all types of women and girls. Talking about “women and minorities” completely ignores the people who are simultaneously both. Girls and women come in all types of shapes and sizes and races and abilities. Not all women are cis women. Not every girl wants to be an astronaut or an athlete. Lipsticks and head-scarves and boots and suits and leather jackets and fuzzy sweaters all need to be welcomed.

- Community engaged research. Projects and studies that meet the needs and answer the questions of real communities will often work better to engage real people than “Hello World” or fighting robots.

- (Here she quoted Antoine de St. Exupery) “If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up people together to collect wood and don’t assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea.” It’s not about specific tasks. It’s not about learning to code or learning calculus. It’s about the endless immensity of the sea. Get people inspired, not about tools but about goals. Not about tasks, but about dreams. (as it turns out, St. Exupery might not have said exactly this. But the point still needs to be made, and I still love it).

- Right to fail. Not just that people have a right to fail, which of course we do, but that it’s right to fail. It’s the exact right thing to do. If you’re not failing, you’re not learning.

(As I said, I’m probably misquoting Dr. Perry, and almost certainly missed some of what she said. 9 points is a start, but only a start. There’s more. But I really love the way she looks at concrete practicalities as well as global principles)

As we at CUNY and all of education and higher education, and as I personally, work to include more opportunities for more people who have been left out of STEM (STEAM), I want to remember these as principles to work with. And I would love to hear more discussion of all of them, at all levels. Let’s talk about specific programs and initiatives, sure. But also about bigger challenges and wider changes that address the real issues.

The Technology of Smarthistory

(A long and technical post follows. If you don’t care to read it, if you’re of the TL;DR school, then go, right now, to Smarthistory.org and take a look at what kind of a beautiful OER can be made with WordPress.)

As anyone who knows me knows, I’m a big supporter (and helper, I guess) of Smarthistory (one of the most important Open Educational Resources on the web). I’ve been involved since the beginning. I’ve posted about it before, more than once. But Smarthistory has just reached another important milestone. For years it was an independent stand-alone website, with several different designs. The original iteration was in WordPress. I built that one, and it looked…well, see for yourself.

That site was the beginning of Smarthistory and it did a lot of the good things that Smarthistory still does. And I was proud to have built it with open source tools and for free. It even won an award, because it did work.

Then there was a small grant and a new design and new site in another open source CMS, ModX. I didn’t build that one, and the design was much better as was the functionality.

That one actually won another award, a Webby, and got a lot more attention. It was a great and beautiful site. Then Smarthistory became part of Khan Academy, and eventually keeping up the separate website wasn’t viable anymore. So the Smarthistory site went to the Internet Wayback machine.

Well, now, once again, Smarthistory is an independent site! Beth and Steven have a blog post announcing and explaining the new setup. And what their goals were.

The new site is even more gorgeous than before–I think–and even more functional. Some of the goals (as Beth and Steven explain) were to make the art the beautiful center, and to use the menus as teaching tools. That point–that information architecture can be a kind of pedagogy, is one that I hope to take up at some length in a later piece. Here I just want to detail, for those who might be interested, just how I made the site happen with WordPress and gave it the kind of elegance and functionality it needed to have.

So let’s dig into some of the technical details.

Smarthistory is running on WordPress, hosted by the wonderful folks at Reclaim Hosting.

Smarthistory is using a child theme based on the Customizr theme. This is a very bare-bones theme, and very clean (letting the images take the stage). It is also somewhat difficult to work with, since it doesn’t use exactly the standard WordPress setup of template files, and all the functions are controlled by hooks…which are sometimes not so well documented.

That child theme uses quite a bit of custom css (and, unfortunately, a lot of the !important declaration. I know that’s not usually best practice, but in this case it was often necessary). In some cases I had to use CSS to duplicate what customizr does for some of its non-template templates. One example of that is the Popular Now page, which, like the Browse by Image pages, came out particularly nicely.

There’s also a rather extensive custom functions.php file. (I’m happy to share both of those, in detail or in full, if anyone wants).

And then there are the plugins…we’re using a lot of standard ones (akismet, for example), but there are some really special ones we discovered and used. Here are the most important–all highly recommended for anyone working on any kind of similar project. Most are free.

Ajax Search Lite provides the really powerful and image-friendly (with thumbnails!) search bar.

Co-Authors Plus allows us to have authors listed for articles (and even more than one author, hence “co-authors”) who do not have to have an account on our WordPress system. Even better, it gives us (with some special help from the great Daniel Bachhuber, formerly of CUNY, who originally wrote the plugin) a very beautiful and functional alphabetical list of all the site’s contributors. And each of them has a particularly nice author page.

Maps Marker Pro let us make custom maps which are so important to telling historical stories.

NextEnd Accordion menu let us have very specific and contextual left-side nav menus, different on different pages (the top-nav is a different plugin–see below).

Ubermenu gave us that top nav. This is an absolutely amazing responsive menu, and when a site has such a large and complicated structure, this is critical.

Of course the site is Creative Commons licensed…and I consider that goes for the technical details, too. So anyone who has questions about how we made things or made them work…I will always share and answer!

To make a site with (literally) hundreds of pages and (literally) hundreds of different menu items, and to make that into a resource that teachers and learners anywhere can use anytime for free…I am so happy and proud to have been involved with that! And I should also mention the great assistance of Gwen Shaw and Nara Hohensee, both CUNY colleagues, who put in long hours and excellent work in getting the site ready for launch.

video player buttons disappearing in wordpress in all browsers

This one falls into the “reminding myself how to do the workaround” category, but maybe it will be helpful to someone else, too.

The WordPress media player has some nice buttons for play, volume, full-screen, and so on. But no matter what I did, I could not see those buttons in any browser. They were there, and could be clicked, but were completely invisible.

The problem is that those buttons are produced as .svg files (scalable vector graphics) and some servers have trouble associating mime-types with those. So the server won’t serve them up (or it serves them as plain text, or something, which they’re not, so they’re not visible), no matter what browser you use.

There are various htaccess tricks to register the mime-type, but I couldn’t get them to work.

However, those same buttons also exist right in the same directory as .png files, which the server is fine with, so I just went to /wp-includes/js/mediaelementplayer.min.css

(UPDATE: It’s now /wp-includes/js/mediaelement/mediaelementplayer.min.css )

and replaced every reference to “svg” with “png.” That did it (had to clear my cache in safari to see them there).

It’s ugly to edit core css like this, and will break every time I upgrade, most likely, so I’ll have to do it again, so that’s why I’m noting it here!

A long and balanced MOOC report

I was interviewed for this report, although my role was small, and now it’s out, and I think worth a read. It’s long, but that means it’s comprehensive. I was impressed by the real openness and curiosity of the researchers and the way they didn’t start with preconceived notions.

So give it a read: MOOCs: Expectations and Reality

Why videos?

In the Cathy Davidson “History and Future of (Mostly) Higher Education” MOOC, I’m really intrigued by her decision (or maybe Coursera’s decision?) to have so much of the content delivered by means of video. Particularly I’m intrigued (or even concerned) by the use of video that takes so little advantage of the affordances of the video medium.

In every one of the videos (all of which are much longer than I would recommend for any online video) I’ve found myself wondering “why does this need to be a video? Why not just text?”

There are so many great examples of educational video which uses what video can do. From the RSA Animate work, to the California Academy of Sciences series on biodiversity (for example). Or of course Khan Academy in general and Smarthistory in particular.

We know so many great ways to make educational video, and we already have text (even with illustrations). Why make videos that just translate text (or even lectures) into video?

I’ve written about this before. And I’m far from the only one. So I’m wondering what was the thinking behind doing things in the Coursera course the way that (at least so far) they’re being done.

In my own course (see particularly the mini-lectures)–not a MOOC, since it was far from massive, but generally open and certainly online, that I taught twice, 3 and 4 years ago, I thought about this a lot and chose to have text with hyperlinks and illustration (and broken down into much smaller pieces, and more readable), rather than me talking to the camera. And we (as a class) discussed that choice and discussed what video can and can’t do (as well as voicethread, discussion forums, audiobooks, traditional textbooks, etc). (And of course, the class used plenty of video, when that was appropriate. Just not video of me talking to the camera).

I really wonder what are the advantages (or at least differences) in having mini-lectures that are like mine (in the “Introductions and Foundations” section or “What is Learning and What is Literature” or any of the others), vs. having me say that same information (maybe with pictures on the side or subtitles) to the camera from a couch with a cup of coffee in my hand.

Creativity vs. Organization

I’m enrolled in Cathy Davidson’s “History and Future of (Mostly) Higher Education” MOOC.

I’ve got some comments about the course in general in another post, but I thought that I might as well share, here, my first assignment for the course. No guarantees that I will keep up with these assignments, but at least I did complete the first one!

The Assignment:

What is one thing–a pattern, habit, behavior–you have had to “unlearn” in your life in order to be able to learn something new? Please write a 500-word essay about what it was you had to unlearn, any challenges you encountered, and any successes you experienced.

My effort:

=============================

As a teacher, I started as a camp counselor and tutor, beginning in 6th grade (my own 6th grade, when I was 12). I did lots of one-on-one work, lots of work about supporting and coaching students, lots of “guide on the side” and almost no “sage on the stage.” I made close connections with students and helped them to come to active learning on their own. I valued creativity (mine and theirs) and flexiblity–meeting students where they were, letting them guide the learning, enjoying a process with them without much emphasis or concern for product.

When I was first hired (almost 30 years ago) as a high school teacher, one of the first major adjustments or “unlearnings” I had to face was the insistence (by the NYC Board of Education) on organization, structure and rigid format. Every lesson, every class, every day needed a lesson plan that had to fit a very clearly-defined template. There was a “Do Now” and an “Aim” (both of which had to be on the board, visible to anyone who came in the room, in every class. When I started as a student teacher, I was told that the principal or a supervising teacher could come into the room at any time and ask to see my lesson plan. If I didn’t have it on paper, in the proper format, or if anything was going on in the class that was not explicitly mentioned in the lesson plan, I could be immediately dismissed…or at least “written up” with a poor evaluation.

As an English teacher, working with students on literature (from SE Hinton to William Shakespeare), on poetry and expression and creative writing, I felt stifled. I felt that I was being asked to kill language, murder learning, torture free thinking, in the ways that I had hated as a student and that I had seen as being useless to my own students. But I needed the job, needed the credential, so I continued. I learned to write plans and state clear objectives and to work backwards from the freedom that I really wanted for students and find ways to create that freedom within the required framework. I even found, eventually, that there were times and there were students for whom that structure was comfortable and encouraging. It turned out that a clear organization and structure could actually be a place where exploration could begin (and through some tricky writing, the written lesson plan could even contain openings, loopholes, where the exploration could be seen to fit).

I didn’t last too long as a high school teacher (seeing copies of The Autobiography of Malcolm X, brand-new and untouched, in the bookroom and being told that they were off-limits because they “stirred students up” was the final straw). And when I went from there to teaching college, I went much more back to my freedom-loving, digression-valuing style (some would say “chaotic”). But when I started teaching online, I found again that organization could be the ally of creativity, and that an online class particularly required a clear organization and a carefully-designed structure…or else there couldn’t be as many of the productive advantages of digression and serendipity.

These days I balance (or struggle to balance) creativity vs. organization, trying to make sure that we have, in every class, the right ratio of both. I like to think that I didn’t “unlearn” creativity, or “learn” organization, either. I unlearned the dichotomy and learned the balance.

========================

Reverse Midterm

This exercise is one that I invented (pretty much on the spur of the moment) last year, when students asked me if we were having a midterm and I hadn’t planned on it. I told them no, then thought it over a bit. The next class I came in and put on a grave and serious face. I started the class by telling them that I realized that we did not have a midterm scheduled, but we still had to have one, so today was the midterm. After letting the moment of panic sink in I told them we would do a different kind of midterm. We talked about the purpose of midterms generally, about questions being more important than answers in a class like this (this is a first-year honors seminar “The Arts in New York City,” but of course I believe the same holds true in all classes). We discussed how a midterm was (could be) a chance to check in and see where the learning was happening and how it was going, but it was also a chance to reinforce and tie together the themes of the course. It seemed that in most cases, they hadn’t really thought of a midterm as something that had a purpose–something connected to learning. It was just something you had to do to get your grades. (in fact, this seems to be true for tests in general. Students–and probably many teachers–don’t use or understand tests as learning tools, only as assessment tools…if that. It’s fun and illuminating to hand students the power to step outside their educational process and and critique the tools and activities to which they’re being subjected. Ultimately, ideally, that leads them to stop being subjected).

So I told them we were going to have a midterm, but it would be my midterm. They write the questions, I have to answer. I told them they could grade me, too. (this led to some moments of real joy).

I started with a brief presentation (about 20 minutes), telling them this was part of my midterm assignment. Sort of an essay question (last year I actually made a Keynote slideshow with pictures of the class activities and screenshots of their own work on the class site. This year I didn’t have time for that, but it didn’t seem like a major loss). I summarized what we had done up to that point in the semester, and gave a little preview of what was coming. This let me sneak in an opportunity to be sure that the students could see and know the through-line of the semester, at least understand that I’m trying to build one and see it develop. Using the presentation for looking back and looking forward let me highlight some of the themes and questions that had been developing (and refer to specific students and specific assignments/discussions “remember when P- was so upset about that photograph?” “Remember when M- showed us the snowy scene outside her house?” “This was when we saw the jazz performance that surprised you all so much.”).

Then I asked them to each write five questions for me. Last year I had each and every student write five questions and it was too many…I couldn’t possibly answer them all. This year I put them in groups and had each group write five questions. I told them they should be questions about the class, either what we had done or would be doing, what they wanted to know or themes they were curious about, and that it was really up to them–it was my midterm exam so I had to answer. I gave them about 7 minutes to write questions. Most groups easily came up with five, although one group only got three, and another wrote ten but told me that they really were most interested in the second five.

After they finished with the questions I asked them to think for a minute about what it would be like if every midterm was like this? They liked the idea…and we talked about how writing a good question means you really have to know and think about the subject (they had just done it in their groups so they knew exactly what I meant). They said “if we could give all our professors midterms like this, we would really know if they know their stuff and we could ask them why we were doing things the way we were. Why we spent so much time on some things and so little on others.”

Then I sat down and read the questions aloud and answered them. I tried to be really honest and think about them as if I was really taking a test (it felt like a job interview, which I guess is the closest I come to taking a midterm these days). I tried to give my best answers, relating to what we had done in class, making connections and modeling how to use a test as an opportunity instead of an obstacle. Part of what I was doing was the “think-aloud” method (widely used and described, but introduced to me by Sam Wineburg) of showing how to approach a question or unfamiliar material. Of course some questions were a little silly, some were impossible to answer, some had premises that I had to question first, so I did all that with real seriousness. I told them how hard it was for me to reverse my usual teacher impulse…which is to throw a question right back at them. I told them (of course they had noticed) that I would usually work hard not to push my own response but to make room for their response. But in this case, since it was a midterm, I wasn’t allowed to do that (several times I caught myself and chided myself and asked them not to “take off points.”)

What happens from this activity right in the middle of the semester is that it ties the class together and engages all of us in the enterprise of the class. We already have a pretty good team vibe by this point, an understanding that the class is something we’re doing together, and this makes it even stronger. (Of course I’m leading the team, I don’t pretend otherwise. But it’s active and inquiry based all the time. The class is not something that’s happening to them or being done to them…it’s not even something they’re “taking.” It’s something we’re making). When students get to think explicitly and critique carefully what’s going on this class, it creates exactly the dynamic I’m looking for in any class. So that’s the purpose of this reverse midterm.

Here (lightly edited) are most of the questions they asked this year. Some were repeated so I won’t type them twice. (you can see that they have definitely absorbed “exam language!” and we talked about that, too).

- How do we find out what are the things we can’t not make (this is a reference to the Adam Savage video we watched which has become a long-standing theme in the class http://macaulay.cuny.edu/eportfolios/ugoretz13/steam/ also related to the Sol Lewitt “Learn to say Fuck You to the World” video)?

- Why can’t everything be considered art? Why do we have to divide things between art and not art?

- Is there a difference in aesthetic quality between art that is confined to an “art place” and art that is all around us in the world? Elaborate

- What is the best form of art?

- In what ways is oral performance considered art and in what ways not art?

- What’s your favorite poem? Why?

- How do you distinguish what makes good photography?

- Which art form do you think is the most honest? Least honest? Elaborate.

- Extra credit: what is your shoe size?

- How can you find art in your everyday encounters?

- Every photograph manipulates/exploits its subjects. True or False? Explain.

- What form of art is the most expressive (Don’t worry, you will get all 20 points for this).

- Is art inspiration or perspiration?

- If you had the power to choose one of your senses to give up, which would it be?

- Draw parallels between a museum, a space for religious prayer, and a playground.

- Is nature independent from art? Why might someone consider nature to be art?

- Is there any art form that you would like to entirely wipe out? Remove from existence?

- Would passionately reading a love letter be a form of oral performance art?

- Why or why not is music the most primitive art form?

- Do you feel that arguing over artistic merit has a constructive purpose? Is arguing about art something that moves art forward or holds it back?

- What is your perception of video games? Are they a form of art?

- Do you believe art and love are related? How so?

- Is grafitti art or vandalism? Defend your position.

I think this “reverse midterm” could work in all kinds of different ways–they could make the questions for other students to answer, instead of me (this year’s students did want me to use these same questions for next year’s class), or we could revisit some or all of the questions as a final which they answer. There are all kinds of tweaks and modifications I want to experiment with. I freely “release” 🙂 the exercise to any and all who want to use or modify or transform.

If all tests were given to teachers, by students…what would that mean for schools? I think often of how we could more closely approach Harmonica High.

Classroom Manifesto

In no particular order, I propose these two dozen….

Questions are more important than answers.

Cooperating is more important than competing.

Thinking is more important than knowing.

Searching is more important than finding.

Making is more important than having.

Opportunities are more important than rules.

Understanding is more important than achieving.

Learning is more important than teaching.

Conversation is more important than studying.

Reactions are more important than rubrics.

Student-student interaction is more important than student-teacher interaction.

Active not passive.

Never ask a question if you already know the answer.

Silence is powerful. Let it go on.

Watch faces.

Don’t repeat what was just said.

Learn ALL the names of EVERY student on the FIRST day.

STEM without Arts is useless and dangerous. STEAM not STEM.

Feelings are always relevant.

Learning is joyous.

Be a person first.

Laugh at yourself.

Care.

The universe is the classroom, the classroom is not the universe.

Protecting Uploaded Files in WordPress

After a long day of struggling with various .htaccess solutions (none of which I could get to work at all in WordPress multisite), I had the wonderful idea to ask for help from the wp-edu listserv and within minutes, Daniel Bachhuber responded with a perfect solution.

After a long day of struggling with various .htaccess solutions (none of which I could get to work at all in WordPress multisite), I had the wonderful idea to ask for help from the wp-edu listserv and within minutes, Daniel Bachhuber responded with a perfect solution.

But maybe I should have started with the problem. (Let’s do it as a theoretical). A professor has a class site in a WordPress install. That professor has permission from the copyright holder (or has the right under fair use) to share a journal article with her class as a PDF. She does NOT have the right to share that journal article with the entire internet. So she scans the article to a PDF, uploads it to her WordPress install, and links to it on a page that is password-protected, giving the password only to the students (and changing it at the end of the semester) so nobody else can access that page.

The problem is that while the page where the link sits is password-protected, the file itself is not. So anyone with the direct URL to the file can download it instantly, without knowing the password at all. What makes matters worse, google (and others) indexes the content of PDFs quite commonly, so even an attempt at security by obscurity of the filename is bound to fail. Anyone googling for the author’s name, or any of the terms in the journal article, would find a quick and easy link directly to the file, which the professor is now, in violation of copyright, giving away free to one and all (I’m not going to get into a discussion at this point of the overall ethics of copyright and whether or not that journal article “wants” to be free).

Extensive searching, extensive trial and error, over an extensive time had left me unable to solve this problem. But Daniel Bachhuber’s suggestion is a simple and beautiful plugin, Ben Balter’s WP Document Revisions. I admit I had come across this suggestion in my googling, but I rejected it without really thinking it through, on the grounds that I didn’t need “document revisions.” Silly me.

The plugin (which works fine and dandy in multisite, although I do recommend the network-admin add-on from the Code Cookbook) with a very simple interface, lets you set the upload directory outside the document root of your site, not accessible to any outsiders, and then it totally respects your password and beautiful permalinks.

It does much more, as a document workflow solution (sort of an open-source alternative to –ugh– sharepoint, in fact). But just for this little purpose, it’s quite nice. Highly recommended!

A Hackable Hole in BuddyPress

Mainly documenting this just so I will have it somewhere I can find it easily, but maybe it will help others, too.

On the Macaulay Eportfolio system we do not restrict account creation by email domain (since we want our students to use whatever email address they want). Instead we use a shared codeword which only our students have. Without that codeword, you can’t create a new account.

This completely shuts down spam blog or account creation (comment spam is a separate issue), but still makes the process easy and open enough for large numbers of students to create (legitimate) accounts whenever they want to from a wide variety of different email addresses and campuses.

But I noticed that every time I upgraded BuddyPress, within 10 or 12 minutes, spam accounts would start flooding in.

The reason is that BuddyPress contains a lurking little file which does NOT respect the codeword restriction. And spambots seem to be scanning for and targeting that file ALL the time.

In the BuddyPress directory, in bp-templates/bp-legacy/buddypress/members there’s a file register.php . And that file is a wide-open invitation to splogs and splusers. Spammers. Bots. They flock to it.

So every time I update BuddyPress, step number one right after the update is to delete that file. I write this to myself…to remind myself to do that, and to remind myself where it is.

Thanks, self.